This paper is available on arxiv under CC 4.0 license.

Authors:

(1) Shrey Jain, Microsoft Research Special Projects;

(2) Zo¨e Hitzig, Harvard Society of Fellows & OpenAI;

(3) Pamela Mishkin, OpenAI.

Table of Links

Abstract & Introduction

Challenges to Contextual Confidence from Generative AI

Strategies to Promote Contextual Confidence

Discussion, Acknowledgements and References

Abstract

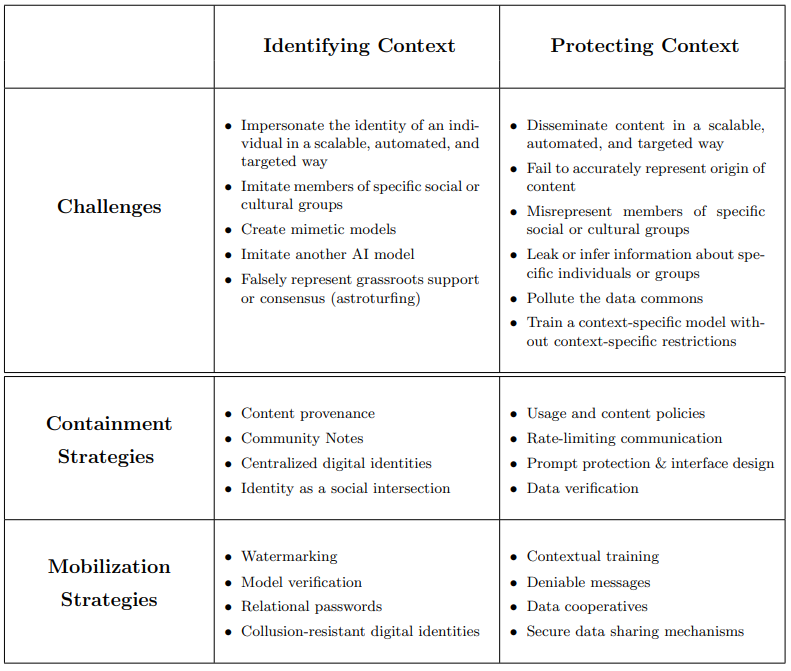

Generative AI models perturb the foundations of effective human communication. They present new challenges to contextual confidence, disrupting participants’ ability to identify the authentic context of communication and their ability to protect communication from reuse and recombination outside its intended context. In this paper, we describe strategies – tools, technologies, and policies – that aim to stabilize communication in the face of these challenges. The strategies we discuss fall into two broad categories. Containment strategies aim to reassert context in environments where it is currently threatened – a reaction to the context-free expectations and norms established by the internet. Mobilization strategies, by contrast, view the rise of generative AI as an opportunity to proactively set new and higher expectations around privacy and authenticity in mediated communication.

1 Introduction

Generative AI is the latest technology to challenge our ability to identify and protect the context of our communications. To see how – and why it matters – it is useful to step back and reflect on the importance of context in communication, and to position generative AI in the sweep of communication technologies that have come before it.

Context is what enables effective communication – it is, in a sense, what binds message to meaning. Consider your most recent face-to-face interaction. Perhaps the interaction was with a close friend, family member, or colleague. Perhaps it was with a perfect stranger. Maybe it was a full conversation, or a brief hey-how-are-you, or even just a nod in the hallway.

Either way, the mere fact that the interaction took place in person likely supplied a common understanding of some basic context. If you or the other person had to summarize the interaction, both of you would likely be able to answer simple questions about where, physically, the interaction took place, on what day, and at what time. Moreover, your answers would likely coincide. You would both be able to describe – at some level of detail – some facts about the identity of the other. Even if it was a perfect stranger, you could likely describe their appearance. If it was someone you’re close to, you might have a refined sense of not only who you were speaking with but also their emotional state at that moment. Rich sensory details, combined with our keen faculties for picking up on contextual cues honed over millennia of social, biological and cultural evolution, power our interpretations of face-to-face interactions – from the most rudimentary greeting from a stranger or acquaintance to in-depth conversations with loved ones and colleagues.

Each advance in communication technology flattens or distorts or rearranges, in its own particular way, the contextual markers available in face-to-face communication. The very first writing systems allowed messages to travel across distance and time, and yet divorced the message from its sender and its occasion. So did the printing press, at scale. Then the telegraph, the telephone and the radio. Then emails, text messages and social media. Each of these technologies broadened the possibilities for communication. And at the same time, each is a mediator, and by definition, mediation compresses context.

In response to each development in communication technology, we develop new norms and expectations to reassert context where it is threatened, preserving our ability to extract intended meaning from the communication. Ancient cuneiform tablets bore a seal impression rolled into wet clay, serving as a signature indicating that a particular individual or institution authored and authorized of the contents of the tablet. Ever since books have been printed, they have included a colophon, detailing facts about the book’s production – the publisher, the date, the city, the press and so forth. Since the early 13th century, paper makers have embedded watermarks in their paper, to signal facts about the quality of the paper or the intended origin and destination of the missive written upon it.[1] Telegrams, like letters sent through the postal service now, were stamped with information about the originating office, and the date on which they were sent.

Our efforts to reassert context in communication don’t always keep up with the contextcompressing technologies, but rather chase a few lengths behind. When Orson Welles, in the early days of radio broadcast, aired a radio adaptation of H.G. Wells’ War of the Worlds formatted to sound like real-time news bulletins reporting a Martian invasion, some listeners believed the fictional events were real, leading to panic. The extent of the panic was exaggerated by newspapers, including the New York Times which reported on a “wave of mass hysteria” – and attempted to discredit their emergent competitors in news provision: “The nation as a whole continues to face the danger of incomplete, misunderstood news over a medium which has yet to prove ... that it is competent to perform the news job” [2]. Regardless of the true extent of the hysteria, the episode underscored the importance of clearly establishing context in a medium that carries both fact and fiction. Following the incident, radio hosts were more careful about providing context to their broadcasts, inserting disclaimers frequently – e.g. when the content is fictional, when the content is a re-broadcast, or when the content is paid for by a sponsor.[2]

We continued our pursuit of context as a vast portion of our communication moved into the digital realm. We invented emojis and deployed them ubiquitously, making our digital communication more expressive through the combination of text and non-text characters. When social media became a leading source of false and misleading information online, we adapted fact-checking measures to this new territory, with tools like Community Notes on X (formerly Twitter), which provide context to otherwise compressed 280 character messages.

Generative AI is the latest technology to upset context in our communication ecosystem. With its ability to mimic human thought processes and replicate human-like interactions, generative AI arguably introduces an unparalleled layer of contextual ambiguity. Voice scams aren’t merely deceptive recordings anymore; they can be highly tailored AI-generated imitations of our loved ones [3, 4]. Catfishing, once reliant on static fabricated identities, now has the potential to deploy dynamic AI personas that can evolve in real-time [5]. Misinformation campaigns, previously limited by human cognitive capacities and speed, can be supercharged by AI algorithms churning out vast amounts of manipulative content at lightning speed [6]. The undisclosed usage of AI models in creating content makes it difficult to discern human from machine, jeopardizing the trust and authenticity we once took for granted in education, commerce, democracy and cultural production.

As we trace the trajectory of communication technologies and the standards and norms that have arisen in response, two key facts about generative AI in 2023 come to the fore. First, generative AI, like – and unlike – many communication technologies that came before, confounds our ability to discern context. Second, the norms governing our experience of AI-enabled communications are inchoate. Taken together, these two facts suggest that we currently face a high-stakes opportunity to develop and deploy tools that establish confidence in context. The strategies we adopt (or not) in the near future may determine whether we regress or progress in our ability to communicate – and therefore whether we regress or progress in our ability to lead rich and differentiated social lives.[3]

1.1 Defining Contextual Confidence

This paper presents an overview of strategies that deserve our immediate attention if we hope to ensure that generative AI improves – or at least does not frustrate – our ability to communicate. These strategies respond to generative AI’s challenges to what we call contextual confidence in communication or information exchange. The context of a communication or information exchange is the “who, why, where, when, and how” of the exchange. Note that context does not include “what” the communication is about – the content of the message is distinct from the context, and context informs how participants interpret the content.[4]

In settings with high contextual confidence, participants are able to both

1. identify the authentic context in which communication takes place, and

2. protect communication from reuse and recombination outside of intended contexts.

With greater mutual confidence in their ability to identify context, participants are able to communicate more effectively. They can choose how and what to communicate based on their understanding of how their audience will understand the communicative commitments of both speaker and sender [8, 9]. With greater confidence in the degree to which their communication is protected from reuse or repetition, participants can more appropriately calibrate what, if anything, they want to share in the first place. When all participants in an exchange have contextual confidence, communication is most efficient and meaningful. This principle mirrors Shannon’s source code theorem: messages can be encoded in fewer bits when the receiver will rely on context, as well as the message itself, for decompression [10].[5]

In recent discussions about the social impacts of generative AI, researchers have enumerated areas of concern that include “Privacy and data protections,” “Trustworthiness and autonomy,” “Misinformation,” “Information harms,” “Information integrity,” “Disinformation” and “Deception,” to name a few.[6] Contextual confidence collects many such concerns under a single heading, by casting authenticity and privacy as two sides of the same coin. Without an ability to authenticate context, we can’t hold people accountable for protecting it. Without an ability to protect context, it may be useless to authenticate it. In the face of generative AI, authenticity and privacy cannot be treated as distinct issues.

In focusing on the contextual norms and expectations that protect information, we draw heavily on the theory of privacy as “contextual integrity” [18]. According to the theory of contextual integrity, an information flow is “private” if it conforms with the norms and expectations that govern information flow to a particular, non-universal audience. Privacy is violated when a “contextual integrity norm” is violated – that is, when information is shared outside its intended context in a way that defies the norms of the original transmission.

Contextual confidence, like contextual integrity, allows for a discussion of privacy that goes beyond “control over personal information,” and also goes beyond a strict “private” versus “public” binary. Instead, it acknowledges a range of “publics” within which participants should be able to expect and respect some degree of privacy and where that privacy embraces not only control of personal information but control of the range of things that might be the objective of communicative acts.[7]

Also like contextual integrity, contextual confidence is both a heuristic framework for determining when needed confidence has been violated and an ideal to which we ought to aspire. We see contextual integrity as an ideal for how communicative commitments to context-specific norms support privacy for specific acts of communication; against the standard of that ideal, we can see violations. Meanwhile, contextual confidence communicates an ideal for the ecosystem of communication. In an ecosystem with high contextual confidence, there is a low probability of violations of contextual integrity. The aspirational yardsticks of contextual confidence and integrity help us evaluate strategies (policies, tools, and technologies) that promote effective communication.

Our framework of contextual confidence speaks to issues related to authenticity in a way that extends from but builds beyond contextual integrity. For instance, “disinformation,” – false or inaccurate information intended to deceive – may be understood as a violation of contextual integrity; it defies a norm of truthfulness that governs many (but not all) communicative acts. But those norm violations, or rather their frequency, will be a symptom of an information landscape with low contextual confidence, where the guardrails that limit violations are not in place. Disinformation succeeds when people struggle to identify the genuine context from which a statement emerges – political propaganda, for example, obscures features of context like who is really behind some message (a political interest), and why the message has reached a particular recipient (because the recipient is a susceptible target for persuasion).

Note that contextual integrity and contextual confidence both deal with disinformation in a way that is distinct from other frameworks like information integrity [19]. Information integrity refers to the reliability and accuracy of information. It suggests that there is a universal benchmark of “accuracy,” and that the public ought to trust high quality information which meets this benchmark.

But the norm that stabilizes communication is not truth but truthfulness – a commitment to communicating only the truth as best as one understands it [20]. A breaking news story may contain statements that are presented truthfully one day – that is, those facts are believed to be true by those who publish them – but then they may be shown in fact to be false the next day. Or truthful but partial accounts may be offered in one context, while people operating in other contexts, when presented with the same facts, might consider them untruthful on the grounds of omission. For instance, in the realm of social media, individuals may want to share certain facts about themselves to one group of people and a wholly different set of facts to another. That social media makes it difficult to authentically present oneself differently to different audiences is a symptom of what internet and media scholars call “context collapse” [21, 22, 23]. Norms of truthfulness can operate and sustain the public sphere, alongside discrepancies and conflicts in information. Supporting contextual confidence requires ascertaining how to help people navigate informational inconsistencies; this navigation is more straightforward when norms of truthfulness, and other allied concepts, can be relied upon.

As discussed above, it is much easier to avoid context collapse – and to ensure high contextual confidence – in face-to-face communication. In in-person communication, parties in the interaction are able to more easily identify context. They can read some basic facts about: who they are talking to (even if they are talking to a stranger), why they entered into the exchange, where and when the communication is taking place. They also understand how they are communicating – in a particular language, body language, dialect, tone, affect and manner. With this context, parties can quickly establish the most efficient way to communicate with one another. For example, consider two strangers who meet and begin to speak to each other in English – one notices that the other speaks with an accent from their home country, and so they switch to their native language, enabling a more expressive conversation. The act of identifying context is the development of a hypothesis about the what, who, when, and why – in this case, the hypothesis includes the sharing of a native language. The act of validation or authentication involves confirming the accuracy of that hypothesis. In this example, the hypothesis is confirmed – and the identification converted into authentication – when the interlocutor responds fluently in the hypothesized native tongue.

In face-to-face communications, features of the context often determine strong norms or expectations about how the communication is protected – i.e. what can and can’t be shared outside of the intended context. For example, close friends who meet periodically to work through details about their personal lives probably assume that what they share will not be repeated widely to others in their network. If one friend recorded the other without their consent, the recorded friend would probably feel that a friendship norm had been violated (and in many places, including twelve states in the U.S., such a recording would be illegal). When being interviewed by a journalist, it is assumed that all statements may be reproduced as quotes in an article unless explicitly classified as “off the record” or “on background.” When there is no obvious norm, for instance at the first meeting of a newly formed interest group, it is common to establish a protective norm. The group may clarify that everything said in the room stays in the room, or the group may choose to follow a looser variant of such a protective norm like the Chatham House Rule.

When communicating from a distance, by contrast, it is harder to establish and protect contextual confidence. Conversing through text, audio or even video alters the rich sense data available that identifies context in a face-to-face interaction. Strangers who begin conversing through text in English may take time to discover that they share the same native language – whereas in person, this can be detected immediately. Online and phone scams target our struggles to identify context. An email that appears to be from a colleague could be from a hacker who compromised their account. A hurried phone call from a family member in trouble could be an AI-generated imitation of the family member, plus a spoofed caller ID.

In addition to the challenges in identifying context, there are a few features of mediated communication that present extra challenges to the protection of context. First, there is often an intermediary – many of our communications travel through intermediaries like messaging services, telecom providers, and social media platforms. To what degree are communications protected from reuse or recombination by the intermediary? Second, the communications are already packaged up for travel, so they can be instantaneously shared outside of their intended context, and often more verifiably so than in-person communications. In instants, an email can be forwarded, a series of text messages can be screenshotted, and a photo, video or audio recording can be sent onward to an unintended recipient. These forwarded artifacts purport to be firsthand facsimiles of the original communication. Compare this lack of protection against digital reuse to the natural protection of in-person conversations – the basic fact that secondhand reports are often met with a presumption of inexactness helps to protect context in face-to-face conversation.[8]

Some of the defining policies, laws and technologies of the last decade can be understood as attempts to reinstate context in mediated communication. Privacy laws like the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in Europe and similar legislation in California aim to safeguard user data and consent. There have been noteworthy pushes for transparency, like the EU AI act, which, for example, demands clarity on why users receive particular content recommendations in recommender systems. In tandem, we’ve seen the rise of authentication tools designed to validate the authenticity of communication sources; examples include DKIM and DMARC for emails, verified badges and content moderation mechanisms on social media platforms. There has been a surge in the adoption of messaging services that provide end-to-end encryption, such as Signal, WhatsApp, and Telegram. Despite these strides, the path ahead towards contextual confidence in mediated communications remains long and complex.

And now, generative AI has thrown a spate of new obstacles onto the path that grow out of and extend beyond the digital communication challenges that have defined the last few decades. Generative AI causes a new set of problems in identifying “who” is engaged in communication: one might be communicating with a model or a human.[9] As models and specialized versions of those models proliferate, there will be a further challenge of distinguishing among different models. For example, a doctor may believe they are communicating with a specialized model trained for clinical use but in fact they are engaging with a model that a malicious actor installed in its place. Furthermore, generative AI models can convincingly imitate specific people or specific types of people. These imitations further challenge our ability to identify “who” we are exchanging information with, as well as our ability to accurately make inferences based on “how” (style, tone, manner) information is conveyed to us.

To see how generative AI also strains our ability to protect context, one need look no further than the training process itself. At the most basic level, very few of us who shared text, images, likenesses, and other content on the internet in the last two decades expected, at the time we shared it, that these data shared in one context (the internet) would be used in a wholly different context (to train a generative AI model). Most of the data used to train the prominent generative AI models was reused, in some sense, outside of its intended context – going forward, it will be important to highlight which communications are used as part of training data for what (general or specialized) model. Not only was our data reused outside its intended context, but now an entity may be communicating about us – the AI model – an entity with which we never formally signed up to be in a communicative relationship. A similar thing might be said about cookies. Cookies communicate to advertising programs about us, and then we receive ads. New options to manage our cookies actually give us the chance to determine what communicative relationships we wish to be part of in the first place. Ideally, we would choose those communicative relationships. And even with those choices there are further questions: What could be inferred about us from the synthesis of various facts about us and our networks? How does the model represent or misrepresent me or the groups and cultures to which I belong?

1.2 Overview

As a framework, contextual confidence inextricably links privacy and authenticity, and clarifies the impact of new technologies on communication. By precisely locating challenges to the identification and protection of context, we can better understand which mitigation strategies are worthy of pursuing and prioritizing. While this paper focuses on generative AI, we note throughout that some of the challenges launched by generative AI are simply turbo-charged iterations of challenges that have existed for decades and in some cases millennia. Other challenges we discuss are different not just in degree but in kind. These challenges arise in interactions between generative AI systems and their users and their audience, and yet they have repercussions for the broader communication landscape. Indeed, a feature of contextual confidence is that it is contagious – low contextual confidence in interactions that involve AI systems generate low contextual confidence more broadly, even in forms of communication that do not involve generative AI.

In the remainder of this paper, we look at the impacts of generative AI on communication through the lens of contextual confidence. In section 2, we discuss how specific capabilities of generative AI present new challenges to contextual confidence. Then, in section 3, we present an overview of strategies (technologies and policies) that can help to bolster contextual confidence. The strategies that we present fall into two categories: containment strategies, which are reactive and help to restore context where it has already been threatened, and mobilization strategies, which are proactive and aim to set higher expectations in mediated communications in the age of generative AI. Table 1 summarizes the challenges and strategies discussed in the paper.

[1] For an insightful history of communication technologies, see [1].

[2] The bodies that govern radio broadcasting also developed rules to enforce the use of such disclaimers. For example, the Federal Communications Commission’s rules were amended to require that broadcasters disclose when content is sponsored (47 C.F.R. §73.1212) and to forbid “the broadcast of hoaxes that are harmful to the public” (47 C.F.R. §73.1217)

[3] One of us has argued elsewhere that generative AI’s threats to communication also constitute threats to the foundations of a “plural” society [7].

[4] Of course, the separation of content and context we insist on here is an oversimplification. In reality, there may be a rich interplay between the two – a journalist may have a clear sense of context that leads her to trust a particular source’s report of some content. But then, if the journalist publishes a statement from the source that turns out to be false, then upon learning that the content turned out to be false, the journalist would in turn have doubts about her understanding of the original context.

[5] To illustrate the interplay between the contextual security of a communication medium and the content of our messages, it is instructive to juxtapose work emails with personal texts. A company-provided email system, inherently formal and transparent, could inhibit frankness. Employees often tread carefully, aware that their messages are not truly private and can be surveilled by employers. These emails are also susceptible to being forwarded, quoted out of context, or inadvertently made public. Conversely, personal text messaging appears more safeguarded, fostering a sense of intimacy and discretion. When a colleague opts to send a message via text over a work email, it may not be merely a matter of convenience. This choice also allows the sender to communicate more freely and precisely, and also indicates to the receiver that the content is potentially sensitive. The recipient, recognizing this context, might infer that the shared information should remain confined to that conversation and treated with discretion. Different conditions of contextual security over text message versus work email give rise to different levels of contextual confidence and expressiveness.

[6] See, for example, [11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16] and [17].

[7] In this piece, we discuss strategies that promote contextual confidence in the sense that they help to set norms around the identification and protection of context. When it comes to protecting context, it is important not only that there are norms, but that the norms are respected. Indeed, a norm cannot be a norm if there is no expectation that it is respected. However, once a norm is in place, there are many ways for norms to be violated. The strategies we discuss in this paper are primarily concerned with setting protection norms, rather than the enforcement of protection norms. We discuss the follow-on need for enforcement strategies in Section 4.

[8] Suppose Zo¨e says something to Shrey in an in-person meeting. Shrey may repeat what Zo¨e said to Pamela, but Pamela will assume that Shrey is not repeating Zo¨e’s statement verbatim – and she may wonder whether Shrey has faithfully summarized or otherwise edited the statement in passing it on. Compare this to the equivalent digital communication: if Zo¨e writes something to Shrey in an email, Shrey may forward the email to Pamela. In this case, Pamela assumes that Zo¨e wrote exactly the text shown in the forwarded email.

[9] The overwhelming focus on making generative AI “human-like” [24] suggests that AI’s impersonation capabilities will continue to evolve rapidly.