Authors:

(1) Reza Ghaiumy Anaraky, New York University;

(2) Byron Lowens;

(3) Yao Li;

(4) Kaileigh A. Byrne;

(5) Marten Risius;

(6) Xinru Page;

(7) Pamela Wisniewski;

(8) Masoumeh Soleimani;

(9) Morteza Soltani;

(10) Bart Knijnenburg.

Table of Links

3 Research Framework

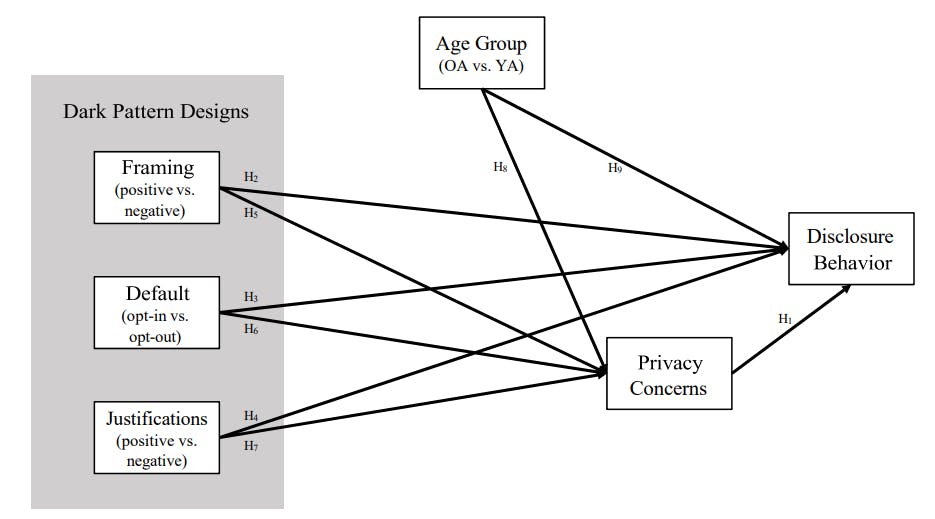

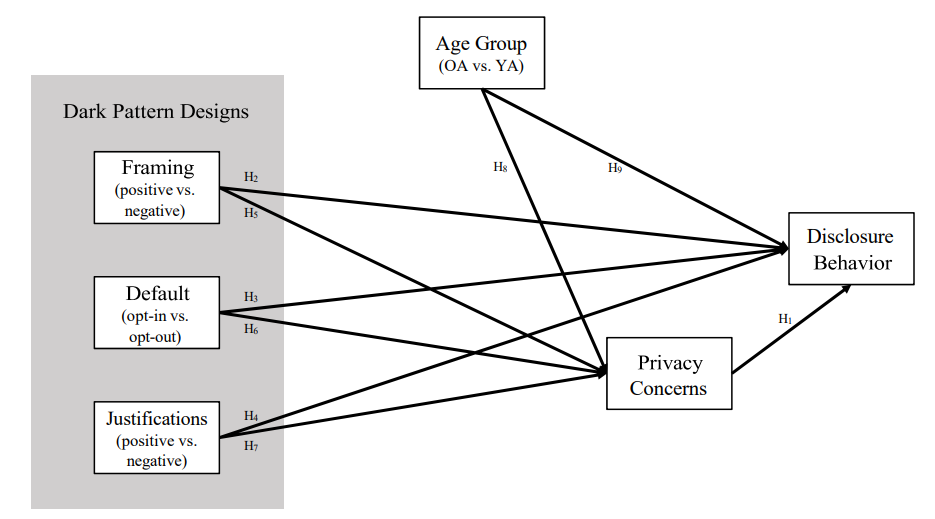

In the sections below, we justify information disclosure and privacy concerns as the two outcome variables of interest when examining the influence of dark-pattern designs. We also explain the 2x2x5 experimental design (where the conditions consist of varying defaults, framing, and justifications). Figure 1 shows our hypotheses via our research model. We investigate these hypotheses using a path model. In a path model, variables can function as both dependant variables (DVs) and independent variables (IVs). In our case, privacy concerns is a DV where we study the effects of dark pattern designs on it, and is an IV when we study how it predicts disclosure behaviors.

3.1 Disclosure Behavior

Oversharing information on social media can lead to negative consequences for users [65]. Therefore, social media platform users employ a wide range of privacy management strategies to manage their interpersonal boundaries, such as managing their relationship boundaries (e.g., by adding a new friend or unfriending someone) and their territorial boundaries (e.g., by tagging or untagging oneself or someone else in/from photos) [94].

Existing literature regards tagging as a form of disclosure [95], since photo tagging can reveal the tagged person’s online information (e.g. name, social media page) to a broader audience when the photo is shown on friends’ timelines. Tagging other people in ones’ photos is a contentious issue [95]: on the one hand, it can increase group cohesion and build social capital [56, 68], but on the other hand, it can lead to an interpersonal privacy violation if the others prefer not to be tagged [26, 81].

3.2 Privacy Concerns

The privacy literature has not reached a consensus about the relationship between privacy concerns and disclosure behaviors. On the one hand, many studies suggest a negative association between privacy concerns and disclosure behaviors [21, 34, 73]. The general argument in these studies is that a high concern for privacy motivates individuals to refrain from disclosing their data. On the other hand, many studies have found that despite their high privacy concerns, individuals freely give up their personal information—a phenomenon that is so prominent that it has been dubbed the “privacy paradox” [8]. The privacy paradox suggests that privacy concerns have little or no relationship with self-reported or observed disclosure behaviors [57, 79, 83]. For example, Tufekci [87] studied students’ self-reported disclosure behaviors on social network sites. Her results show “little to no relationship” between online privacy concerns and disclosure on online social network sites. Despite these contradictory findings, we pose the following hypothesis reflecting the base expectation that privacy concerns are predictive of disclosure behaviors:

H1: Individuals with higher privacy concerns are less likely to disclose.

In the following two sub-sections, we build on our RQ1 by posing six hypotheses about the relationships between dark pattern design, disclosure behavior, and privacy concern. We then address our RQ2 by posing two hypotheses regarding the effect of age on disclosure behavior and privacy concerns.

3.3 Behavioral Effects of Dark Pattern Designs: Inducing Disclosure

In this section, we discuss the behavioral effects of framing, defaults, and justification messages. Particularly, we draw upon the “privacy dark patterns” literature to hypothesize how these design features are being used to increase disclosure.

3.3.1 Framing and Defaults

Framing and default effects have been extensively studied in the privacy domain. Johnson et al. [30] and Lai and Hui [43] independently found framing and default effects to have a significant impact on users’ decisions. In both studies, a positive framing and an opt-out default setting increased the likelihood of users accepting the disclosure requests. In line with these findings, we study two conditions of framing (positive “tag me in the photos” vs. negative “do not tag me in the photos”), and two conditions of the default (opt-out vs. opt-in). We hypothesize the following:

H2: A positive framing will increase disclosure.

H3: An opt-out default will increase disclosure.

3.3.2 Justification Messages

Existing literature suggests that prompting individuals with a message about a product or service can influence their decisions in favor of the message content [27, 39, 45, 92]. Dark pattern designs sometimes use this feature to promote disclosure [12, 54]. For example, they show messages about a product’s popularity in the form of reviews [17] which can sometimes be fake and misleading [80, 84, 91]. Hanson and Putler [27] showed participants a normative justification: an arbitrary integer ostensibly representing the number of downloads of a software program. Participants who saw a higher number were more likely to download the software for themselves. This is arguably due to a herding effect [6], where individuals follow the footsteps of the majority. In addition to such normative justifications, dark pattern designs sometimes use descriptive justification— pushing the benefits of the product—to promote product use or disclosure [12, 54]. For example, in the context of a travel advisor app, designers prompted users with a message of “by signing in, you can download over 300 cities, locations, and reviews to your phone” [12]. Reading about the benefits of the product is arguably a motivating message to sign in and use the app. Having higher quality reviews will increase the likelihood of one buying an online product [39], or talking about the effectiveness (pros) of treatment rather than the cons will increase the likelihood of accepting it [10]. In line with these findings, we study five conditions of justification messages (positive/negative normative, positive/negative rationale-based, none). We pose the following hypothesis:

H4: Positive (as opposed to negative) justification messages will increase disclosure.

3.4 Attitudinal Effects of Dark Pattern Designs: Inducing Concerns

The effects of framing, defaults, and justification messages on disclosure behavior are evident in the literature [1, 5, 27, 30, 33, 43]. The compliance-inducing effects of such design interventions meet the goal of dark pattern designs. However, research shows that the behavioral effects of these dark pattern strategies may not actually map to their attitudinal effects [7, 38, 41]. In this section, we examine the effects of dark pattern designs on individuals’ state of privacy concerns. Privacy concerns are often measured as an individual trait, rather than a dynamic state [73]. However, this assumption may not be valid. Few studies consider privacy concerns as a dynamic state [67]. We further contribute to the literature by highlighting this perspective and presenting privacy concerns as a dynamic state which can change in response to different design strategies.

3.4.1 Framing and Defaults

Online firms have an incentive to collect as much data about their users as they can. Data is an important asset in the industry [13, 29, 78]. For example, having data about customers’ preferences and needs can help firms better target their advertisements to individuals likely to need their product and avoid the unnecessary costs of contacting consumers whose preferences do not match the product [29]. Therefore, some companies adopt dark-pattern design strategies to collect more user data [12].

Framing and default are compliance-inducing mechanisms [4] that are often used in dark pattern designs [25, 53, 54]. Dark pattern default options are designed to encourage sharing of personal information and to maximize online firms’ collected data [12]. Likewise, dark pattern designs use positive framing in the choice statements to endorse disclosure [54]. Whereas the behavioral effect of such dark pattern designs are outlined in Section 3.3, here we note how these interventions can adversely influence users’ attitudes towards the system [12, 47]. For instance, Knijnenburg and Kobsa [41] found that an opt-out default would increase perceived oversharing threats compared to an opt-in default. Therefore, we pose the following hypothesis:

H5: A positive framing will increase privacy concerns.

H6: An opt-out default will increase privacy concerns.

3.4.2 Justification Messages

In the context of dark-pattern design, we argue that while a positive justification message might be intended to encourage individuals to use an app or increase disclosure, it could also increase users’ privacy concerns, especially when they realize that the justification message is used as a dark-pattern strategy. Conversely, users may find a negative justification (i.e., cautioning them about the cons of the product) a sincere message [38] that is indicative of the developer’s benevolence and/or integrity (two of the primary components of trust [55]). For example, communicating potential risks in a study report will increase its perceived trustworthiness [72]. Since trust and privacy concerns are inter-related [19], we argue that a negative justification will result in lower privacy concerns:

H7: Negative (as opposed to positive) justification messages will decrease privacy concerns.

Next, we explain the effects relating to age and our second research question.

3.5 Examining Differences between Older Adults and Young Adults

Literature suggests a positive association between age and privacy concerns, indicating higher concerns for older users [90]. However, the literature shows mixed findings in terms of the main effect of age on disclosure behaviors. While some studies do not report a significant relationship between age and disclosure [35], other studies show higher disclosure rates for older adults [71]. Despite these mixed findings, we pose the following hypotheses to investigate these effect:

H8: Older adults will have higher levels of privacy concerns than young adults.

H9: Older adults will disclose more information than young adults.

3.5 Examining Differences between Older Adults and Young Adults

Literature suggests a positive association between age and privacy concerns, indicating higher concerns for older users [90]. However, the literature shows mixed findings in terms of the main effect of age on disclosure behaviors. While some studies do not report a significant relationship between age and disclosure [35], other studies show higher disclosure rates for older adults [71]. Despite these mixed findings, we pose the following hypotheses to investigate these effect:

H8: Older adults will have higher levels of privacy concerns than young adults.

H9: Older adults will disclose more information than young adults.

To the best of our knowledge, we are the first to study the difference between older and younger adults responses to the dark pattern designs.

This paper is available on arxiv under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 DEED license.